The Intersection of Risk Assessment, Risk Communication, and Environmental Justice

By Bridgette R. DeShields, Principal, Technical Director, Permitting and Planning

Mala Pattanayek, Senior Consultant

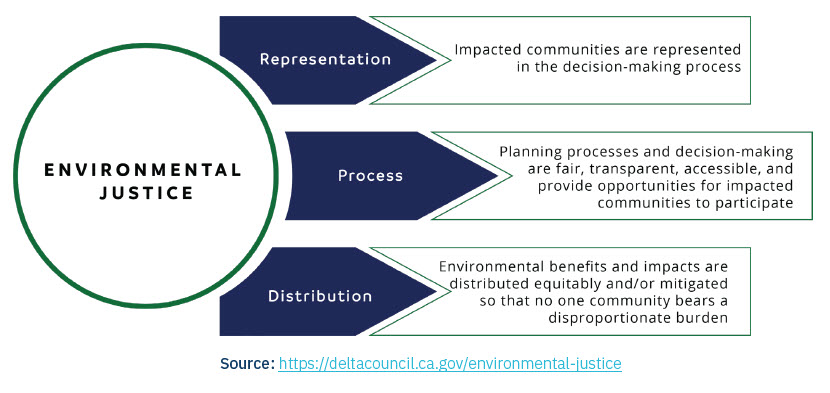

At first glance, the practice of risk assessment and the topic of environmental justice (EJ)1 seem at odds. The goal of human health risk assessment is to identify and evaluate those populations, subpopulations, and individuals at greatest risk. EJ principles consider providing the same level of protection from environmental and health hazards for all communities, taking into account the existing degree of environmental degradation in overburdened and disenfranchised communities (e.g., low-income, minority). These communities could be both more susceptible and more exposed to many environmental pollutants.

Risk assessments are used in the decision-making process for practically all environmental regulations, including site remediation, facility citing, and chemical approvals and management. The methodology used in these assessments partially determines the treatment of issues of concern in communities disproportionately affected by environmental hazards. Risk assessment practices can readily be adapted to address differences in vulnerability and susceptibility among populations with differing socioeconomic status. And risk communication is a thread that unites the two types of evaluations (i.e., risk assessment and EJ).

Risk assessment is purportedly an objective scientific process, yet the data gaps, selection of assumptions, and related uncertainties impact whether the results truly represent unbiased assessments. Furthermore, risk management decisions are often made in the absence of or discounting public input, especially when it is viewed as “unscientific.” In general, risk assessments are biased to the “conservative” or protective end of the spectrum, with sensitive or most vulnerable receptors (e.g., Tribes and subsistence fishers exposed to contaminated sediment) considered in setting exposure assumptions and certainly in the promulgation of toxicity criteria. However, scientists, engineers, and regulators perceive the concept of “acceptable risk” in a different manner than community members do. Risk assessment under current federal and state statutes supports risk management decision-making, but considers neither the cumulative effects of chemical and nonchemical stressors nor other intrinsic (e.g., chronic health conditions) and extrinsic (e.g., food insecurity, poverty) risk modifiers. As a result, community members often do not trust that the risk assessment considers the nature of overburdened or disenfranchised communities, largely because this consideration is an inherent part of the risk calculations and is either not explicitly described or is not described in a manner understandable by the layperson.

One way to bridge this gap is effective outreach using risk communication principles.2 Successful engagement requires building trusting relationships, explaining science in lay terms without being patronizing, and demonstrating to the community members that they are not just an afterthought. It also means considering alternatives, implementation methods, and control measures above and beyond the minimum necessary, as well as emphasizing transparency in reporting.

There are several methodologies available to incorporate EJ in environmental assessments. Some focus on populations, and some focus on policies. They vary in terms of quantitative and qualitative approaches and the degree of community engagement.3 Regardless of which methodology is used, an EJ assessment and framework should be established during the planning process of a project (e.g., prior to or during the feasibility study phase) and not at the end (e.g., just prior to or during implementation), which tends to be more typical. Community engagement needs to be meaningful, early, often, and especially prior to critical decision-making points of the process. The community needs to feel that it has a real voice. And those voices need to be woven throughout the decision documents.

1EPA defines EJ as “The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

2Principles of Community Engagement published by the National Institutes of Health offers ways for practitioners to plan, design, and implement community engagement efforts: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf.

3Solomon et al. 2016. Cumulative Environmental Impacts: Science and Policy to Protect Communities: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021807.